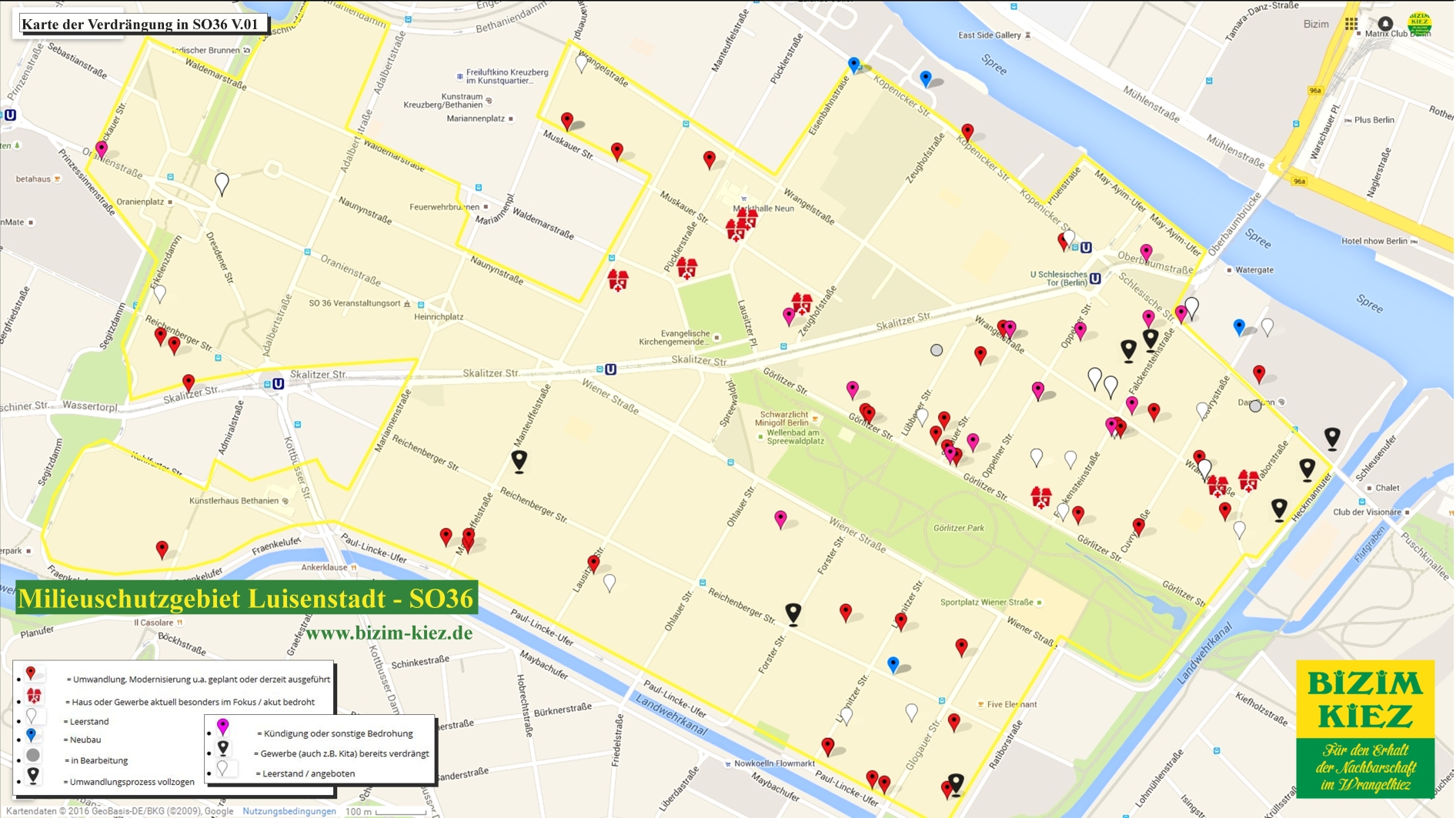

Collecting and adding personal experiences of displacement

We want to use the map to capture the extent of the pressure on us. We need information on the companies involved, and to find out about their methods. The names of contributors need not be made public, if preferred.

or simply post it right into our mailbox at 77 Wrangelstraße

Disclaimer

tips when using the Map

Background to the map –

making the experience of displacement visible

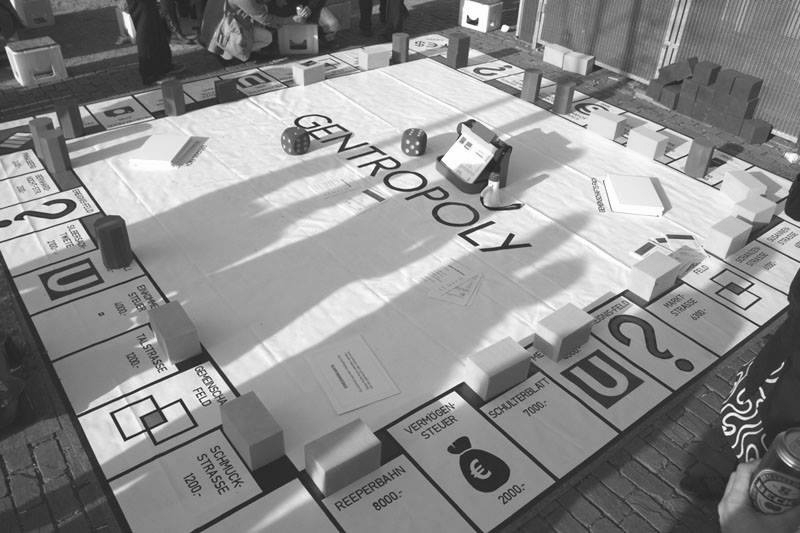

Over the last few years tourism and real estate trends have made the area into one of the “hottest“ parts of Berlin – and not just because of the clubbing scene. This has attracted big “investors“, or to put it better: dubious corporate structures specialized in “unique apartment buildings in top locations“ and “apartment blocks with development potential“.

The “methods“ employed are mostly just tricks to put pressure on tenants

If a building falls into the hands of one of these investors it largely means worries and insecurity for the residential tenants or, for commercial tenants, as with Bizim Bakkal, a sudden termination of contract and the threat of the loss of one’s livelihood. An investor’s first priority is always profit. If the apartments and commercial premises are empty they can be made into all the more lucrative investment properties. As a result warnings and terminations of contract are issued, and eviction suits filed. Although German tenancy law provides protection for residential tenants, in practice regulations like the new brake on rent prices introduced in 2015 prove ineffective. Politicians seem unable to cope with the issue, and do not make effective use of the options available to them. For instance, there is not a single law obliging property owners to respect the public good. The carving up of older residential buildings, which for decades have been made up of communities of tenants (85% of Berliners live in rented apartments – many buildings are more than 100 years old), and their conversion into owner-occupied apartments solely to increase profits, is one of the approaches taken. Using state-subsidised energy-efficient renovation to justify virtually unlimited rent increases is the other. There has not yet been any capping of rent increases imposed on the basis of authorized modernization. Cases of tenants having to pay 270 euro more per month so as to save 70 euro in energy costs are a clear illustration of the absurdity of this. Many a tenant wakes up one morning to find their apartment darkened by scaffolding and a tarpaulin placed up against their window overnight, and their home is quickly transformed into a kind of solitary confinement. This is just one example of the methods deliberately used to wear down tenants psychologically to get them to move out. Modernization can eventually lead to unaffordable rent increases – with rises of several hundred percent imposed in some cases. Here tenants are initially gtreatedg to balconies and elevators, but are then later charged a high price for them, even though they often go unused. Because what people need first and foremost are the social fabric, humanity and neighbourliness that they have spent years building up together – in a word, the „Kiezg – and not constant worries about being displaced.

Maximizing returns on investment is incompatible with Kiez life

Here added value means a form of community living which in other places has already been renovated away with uniform facades, and where the social face has already been gambled away. In many commercial yards in Kreuzberg the loss is also apparent: workshops and print shops, model builders and electricians have disappeared, just as the independent retailers in Wrangelkiez have been coming under threat for some time now – Ahmed Çaliskan and his shop Bizim Bakkal is not the first instance of this.

But we must wake up to the fact that it is we who have created that which others now want to sell. It is not in our interest to let unscrupulous investors grab the added value for themselves, but rather that added value must go to benefit the community living here. Not in monetary form, but in the form of a shared future. Berlin’s current development is set to divide it into two residential classes, meaning that the rich live in one place, and the poor live where they are forced to live, or wherever the last remaining accommodation happens to be, says Andrej Holm, a researcher on gentrification at Humbolt University, for example.

www.rbb-online.de/stilbruch/archiv/20150219_2215/kreuzberg-wird-verhoekert-reportage-gentrifizierung.html

The Map of Displacement is initially aimed at visualizing individual cases, and subsequently as a tool to facilitate the development of appropriate strategies and approaches.

But positive examples and projects can also be incorporated. The Map should be seen as a continuing process, where each of us is requested to contribute (melden@bizim-kiez.de). This particularly applies to those directly affected. (Contributions can, of course, be treated anonymously if preferred.)

The Map is a tool for finding each other and for networking to facilitate community resistance, and will probably also be linked into other Berlin maps dealing with gentrification, and their associated initiatives.

Translation by Anthony

Disclaimer

tips when using the Map